Presentation by the Honorable Charles M. Honeyman (Immigration Judge, Retired)

What is a Court?

Cambridge Dictionary: a place where trials and other legal cases happen (with) …officials deciding if someone is guilty

Merriam-Webster: formal legal meeting in which evidence about crimes, disagreements, etc., is presented to a judge and often a jury so that decisions can be made according to law.: a place where legal cases are heard

Dictionary.com: a place where justice is administered; a judicial tribunal duly constituted for the hearing and determination of cases

Wikipedia: A Court is any person or institution, often as a government institution, with the authority to adjudicate legal disputes between parties and carry out the administration of justice in civil, criminal, and administrative matters in accordance with the rule of law.

Imagine that you were going to consult on the establishment of a new specialty court for a country transitioning from authoritarian rule to a western style democracy consistent with the noble aspirations of our imperfect Constitution from which our country sprung and struggles to improve upon.

Would you start off by placing the judges and prosecutors in the same government department whose director supervised both of them? Of course not.

Well, that was the Immigration Courts’ status prior to 1983, with both the Immigration Judges and prosecutors serving as employees of the I.N.S., whose director was their effective supervisor. Immigration Judges had only been recognized as “judges” and not just “special inquiry officers” for a short number of years.

Did that cozy structure make sense and promote impartiality and due process in decision-making? Of course not.

Out of necessity, those early judges banded together to form an association that became the NAIJ, an NLRB recognized collective bargaining unit in 1979.

Resisting political pressure from some quarters for greater independence of Immigration Judges, on January 9, 1983, DOJ created EOIR in order to at least ensure some separation structurally from INS which prosecuted the cases. Nevertheless, both components’ ultimate supervisor was the nation’s chief prosecutor, the politically appointed Attorney General of the U.S.

Ideally, would you really recommend such a structure, where the judges and the trial level prosecutors report to the nation’s chief prosecutor and suggest to a fledgling democracy that management would somehow be fair and vigilantly ensure that the judges remain impartial, without feeling direct or subtle political pressure? Of course not.

So let’s say that later, following an attack on the hypothetical country, there is a security need to expand and reconfigure immigration benefit and enforcement functions in a new department (for us, that is the sprawling DHS created in 2003), leaving behind the judicial functions (for us, EOIR’s Immigration courts and the BIA), in the old department, headed by the nation’s chief prosecutor. Would you ever endorse such a structure whereby the chief prosecutor would naturally side with trial level prosecutors now employed by the new department, overruling his own “judges” or worse, be permitted to rewrite appellate decisions or worse still, permit a non-judge subordinate administrative director to decide appeals? Of course not-that would make a mockery of the idea that these were “courts” in any meaningful sense.

Here’s the key take away-the housing of career administrative Immigration Judges and Courts within the politically headed Department of Justice is, and has always been, a structural flaw, making them vulnerable to political interference, which the current administration has exploited. But this is not the first time.

During President George W. Bush’s administration, in the context of the investigation surrounding the firing of U.S. Attorneys, through the May 2007 testimony of former White House counsel, Monica Goodling before the House Judiciary Committee, it came to light that political considerations-that is, whether the applicant was a Republican or a conservative loyalist- were taken into account in their evaluation for non-political career positions, including Immigration Judges. But let us be clear, the potential for exploiting this structural flaw is there regardless of which party occupies the White House.

An example of this bipartisan tension between Immigration Judges and the government can be seen in the efforts by the administrations of both major parties to decertify NAIJ, arguing that the judges are “managers” who can’t form unions under the Federal Service-labor management relations statute. In 2000 and in 2019-20, both the Clinton and Trump administrations filed unsuccessful petitions with the Federal Labor Relations Authority (FLRA) seeking such decertification. An appeal to the full FLRA board was filed earlier this month relative to the most recent effort. So what is the reason for this historic bipartisan hostility to public sector unions? Quite simply, there are forces within the executive branch agencies such as DOJ, including both career and political appointees, who do not want to be compelled to bargain, negotiate, or collaborate with NAIJ. It’s all about power, control, and in the case of the Trump political appointees, a nationalist inspired agenda to dramatically reduce eligibility for most immigration benefits under current law, wiping out decades of case law through proclamations, executive orders, and revised regulations, much of which it is believed would not be supported by NAIJ leadership and a significant number of Immigration Judges committed to due process and fundamentally fair hearings.

But there’s even more evidence of the historic bipartisan hostility to Immigration Judges that is possible because of their structurally weak position, making them vulnerable to the political class and the stronger institutional position of DHS (and previously INS). The significant immigration reform act of 1996 included the first statutory mention of Immigration Judges, previously referenced only in regulations; moreover, the new statute provided Immigration Judges with monetary civil contempt authority, following regulations that were to be published by the Attorney General. However, due to hostile forces within DOJ, particularly INS and later DHS, that resisted the idea that their attorneys should be subject to sanctions by mere Immigration Judges, implying that only private attorneys could be sanctioned, no regulations were ever published and thus our government has thwarted the will of Congress and consequently the people.

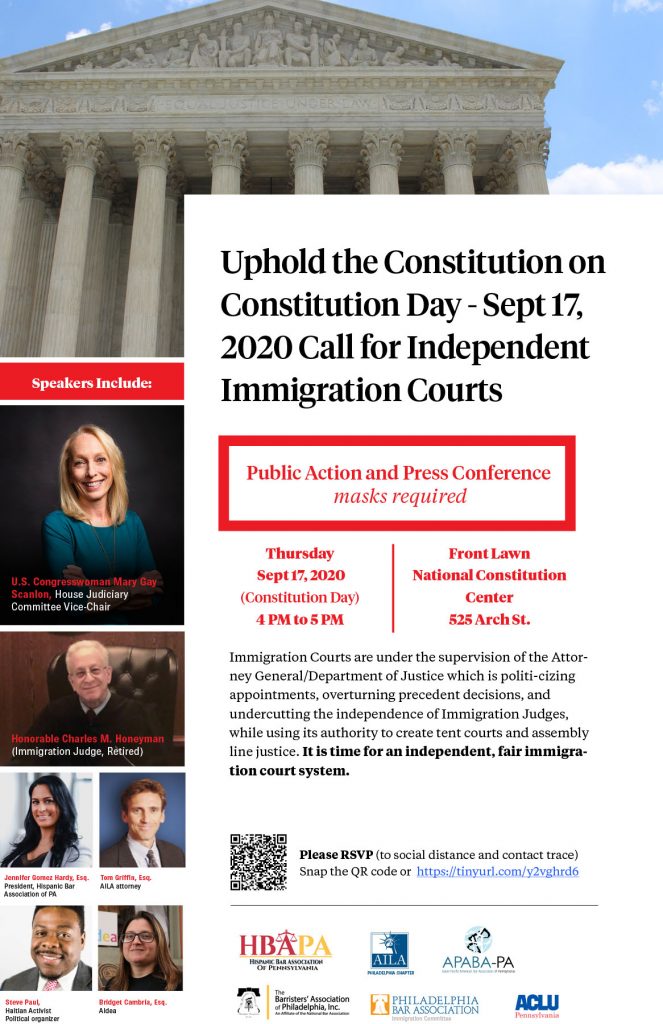

So in today’s polarized political world, as manifested by the brazen actions of this administration’s Justice Department, including the politicized hiring of career professionals, the need for an independent Immigration Court under Article 1 of the U.S. Constitution, which is celebrated by the center in whose shadow we humbly stand today, could not be more compelling or urgent. Moreover, it is supported by most major institutions within the legal community and a growing number within the political class.

What if I told you that there was a duly appointed, scholarly, well credentialed Immigration Judge who, upon receiving a decision from the Attorney General of the U.S., concerning whether a juvenile had received adequate notice of a prior hearing, had the temerity, the audacity, to request that the government, through DHS and those representing this young boy, file legal briefs before issuing his final decision. What if I told you that politically motivated decision makers, probably up the chain, at least through the agency’s Director, probably through the Attorney General or senior staff, and maybe even higher, rather than waiting for the briefs, the judge’s decision, and any appeals or motions that might follow consistent with applicable law, ordered that the judge be removed from this case (and 80 or more similar cases), and that a management level supervisory judge be assigned and sent for one day to the Philadelphia Immigration Court to conduct a five-minute hearing, ordering the boy removed in his absence without waiting for the aforementioned briefs. And no, we’re not talking about the absence of the rule of law or the politicized governance that reflects and infects the reality of today’s Belarus or Russia. It bleeds throughout the corrupt anti-immigrant xenophobic fabric of Trump’s America.

When Judge Steven Morley, about whom I’ve spoken, and I were sworn in as Immigration Judges (for me 25 years ago this month), we took an oath to defend America against all enemies, both foreign and domestic, never thinking that among the latter, might be those for whom we might someday serve.

Republicans and Democrats. Support an Article 1 Immigration Court, with a firewall between its judges and executive branch political appointees. It’s just, it’s fair and, in today’s context, it’s what those men, pledging their lives and sacred honor in that building there, would want. Due process demands it!

Thank you.

Hon. Charles M. Honeyman (Retired) serves as Of Counsel at Palladino, Isbell & Casazza, LLC, after more than 24 years of service as an Immigration Judge. Following his retirement, Judge Honeyman has remained active in the field of immigration law through writing, speaking, teaching at CLEs, and offering strategic litigation counsel, and advising academic scholars conducting research on immigration-related topics. Judge Honeyman is a retired member of the National Association of Immigration Judges (NAIJ), a member of the prestigious Roundtable of Former Immigration Judges, and has rejoined AILA. Judge Honeyman is a member of the Maryland (active) and Pennsylvania bars and was formerly a member of the New Jersey bar.

The materials available on this website, including third-party links, are provided for general informational purposes only. They do not constitute legal advice and we make no representations as to the accuracy or completeness of any information on this site or found by following any link on this site. This website is not intended to create an attorney-client relationship between you and Palladino, Isbell & Casazza, LLC (PIC Law). You should not act or rely on any information available in or from this website without seeking the advice of an attorney.© Palladino, Isbell & Casazza, LLC (PIC Law). All Rights Reserved. The materials and images found on this site, produced by Palladino, Isbell & Casazza, LLC (PIC Law) are copyrighted and shall not be used without advanced permission. For permission, contact us at info@piclaw.com.